I’ve temporarily fled the pollution of the Kathmandu Valley and am back home in England for a few weeks. This has given me the chance to give some talks and my first was to a class of Year Fives in a Cambridge primary school. My presentation was based on my children’s adventure stories set in Nepal and as the books are populated with wildlife stars, it seemed fitting to describe some less well known Himalayan animals and get the children guessing the species. The children were wide-eyed and seemed to love my stories. My favourite question from my audience was, “did it take you more than a whole day to write your books?”

I was also invited to lecture another set of Year Fives but this time they were medical students. Undergraduate medics – especially Cambridge students – are exceptionally gifted at absorbing facts and passing exams, and take their studies very seriously. This stimulated an urge (arising from the mischievous little girl that is still within me) to tease them for their fact-hunger: challenge them to think and discuss. I wanted to address them as I had the other Year Fives, “Now children, I want to tell you about a creature that makes a

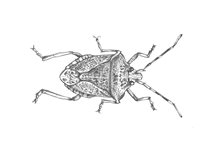

horrible smell if it feels threatened (no, no, not a skunk) or if happens to fall into your tea – indeed before it dies it renders the tea so badly tainted, it is undrinkable. Do you know what kind of animal it could be?”

Of course, I didn’t start like that. I was there to talk about the challenges of training health workers and of the tremendous difficulties there are in improving health and healthcare in low income countries. I gave an example from Nepal where health professionals are forever going on “trainings” but although participants say how much they enjoyed the experience – especially the snacks and freebies – such workshops and short courses aren’t terrifically effective at improving clinical skills, critical thinking and problem solving.

“I was sitting at the back of this august lecture theatre during the previous presentation,” I told them, “and observed that many of you had your laptops open and at least half appeared to be taking notes but others were booking cinema tickets, on-line shopping, looking at Pinterest, checking emails and a couple of people were even gaming. This nicely illustrates how even when people attend lectures and training events they are not necessarily listening to any of it.”

Students looked at each other and there were embarrassed smiles and some laughter.

I went on to describe some of the clinical mentoring I’ve been doing, working with Health Assistants and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives employed by the impressive charity PHASE Nepal. PHASE employ bright and highly motivated young men and woman who support Nepali government health workers in helping provide 24/7 clinical services in remote mountain communities. They are all many miles from home and loved ones: parents, husbands, children.

The health workers function as GPs but they also have to deal with the results of accidents, complications of pregnancy, malnutrition, psychiatric emergencies and indeed any medical problem that occurs yet they have little backup and limited scope for prompt evacuation. Furthermore, sending a patient to hospital could mean organising two teams of four men (one foursome carrying, the other ‘resting’) to stretcher the casualty down the mountain. This can involve negotiating narrow paths cut through vertical cliffs above 2000m drops. Then once they reach where the nearest dirt road they’ll cadge a lift on a truck.

By this point, the medical students seemed less interested in their laptops and some were positively wide-eyed and rather reminded me of the other Year Fives.

I hoped they left our session a little wiser (if not fully fact-stuffed) and even if they asked less interesting questions than the primary school children. I really hope that the talk got them thinking. Those of us who live in the UK know that the NHS may be struggling but we do still have an excellent health system and there’s always scope for prompt evacuation to a good hospital if things go badly wrong. And many of us have reason to be grateful for that.

Thanks to Betty Levene for the excellent drawing of a stink bug, which is featured in the adventure books

Himalayan Kidnap and

Himalayan Hostages.