APOLOGY

This piece, published in the

Epsom and Ewell Advertiser on 23

rd September 1976, was my first foray into travel writing and I have gritted my teeth and resisted an almost overwhelming urge to edit, improve and punctuate it. It is as first printed except that I have inserted a few [parentheses] in order to explain better the context. Even the journalist's introductory paragraph isn't great writing nor is it properly punctuated.

I hand-wrote this article, folded it into a suitable envelope and sent it from some remote Pakistani post office somewhere. I was 22 at the time: naïve, ignorant, opinionated yet absorbing experiences that were ultimately responsible for talking my way into medical school and following a career that contributed to improving the health of people in Asia and the UK.

¤

HAIRPIN BENDS & WASHED AWAY ROADS

Young Stoneleigh ecologist Jane Wilson, set off in July1976 from her home in Sparrow Farm Road, to further research in the Himalayas.

This is her first report to the Epsom and Ewell Advertiser

of the expedition where she is studying the bats and bugs in the caves in Pakistan, India and Nepal.

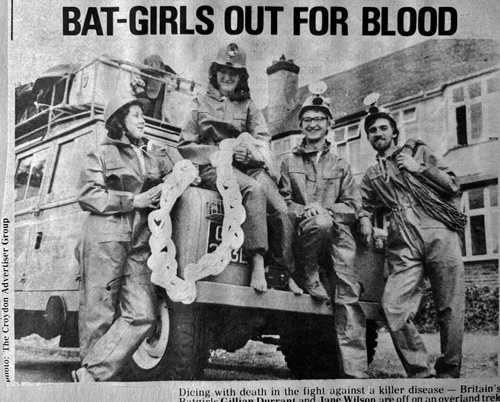

Jane, 22, joined three other young researchers for the trip. Gillian Durrant (botanist), Christopher Smart (surveyor) and John Turner (engineer).

She was awarded a Churchill Memorial Fellowship for her research to help fund the trip which took her two years to plan.

Readers may recognise Jane as a librarian at Bourne Hall, Ewell, where she worked for a short time before the trip.

|

| Jane, Gill, Chris and John and his trusty Land Rover ready to set off for the Himalayas |

I became ‘doctor’ to the Kalash

The tourist information brochure showed the route from Peshawar to Chitral and beyond as metalled. But about 75 miles out of Peshawar the road became gravel-topped. And in over 100 places in as many miles the road was washed away.

By driving down into the riverbed, we [in a nine-year-old long wheelbase Land Rover] were able to negotiate these little impediments while these sections were being repaired by local and imported labour.

The track wound its tortuous way up to the 10,500ft Lowari Pass. The view from the top was incredible – hardly comparable with the notorious [but not especially impressive] Khyber Pass that we’d driven through four days before.

As goose pimples appeared, we felt pleased to have got so far along a route that was “impassable” for Land Rovers. We were sure that the rest of the 200-mile three-day journey to the capital of this mountainous district must be straightforward.

¤

Hairpins on the Chitral side of the Lowari Pass were tighter and more slippery and steeper; several needed to be tackled with three point turns. As the Land Rover wheels crept close to the edge we wondered how trustworthy Pakistani road engineering was!

As the road wound down another turn [at an ice-filled gully] we came across yet another blockage. Twenty or so bare-foot Pakistanis were dashing around, shouting, shoving and shovelling ice and rocks to release a truck that had become wedged at the bottom of a small glacier.

Deciding that we had a long wait ahead of us we broke out entrenching tools and set about creating a bypass.

Soon we had half a dozen helpers. When we tried our new road the ice under the boulders gave way and for a fraction of a second the Land Rover tottered on the edge. Chris and Gill’s frantic pushing kept the Rover upright and with a little more road building we were soon back on the main track, pushing on to be held up only by the occasional pause for blasting work [by engineers, not us].

|

| Decending from the Lowarie Pass, bypassing the suck truck surrounded by ice |

We set up base camp in a hotel garden in Chitral [town] and decided to take a jeep-taxi to Garam Chasma – a village with a hot spring 28 miles north of Chitral, within 30 miles of the Afghan border and 30 miles from where it was shown on the map.

With 11 passengers the jeep was somewhat overloaded. Two were hanging on to the back and one sat to the left of the driver of this left-hand drive vehicle.

The journey, if uncomfortable, was uneventful. We only had to walk one stretch. We drove up the Lotkhu river valley gorge and through a band of limestone near Shoghore. Our spirits rose when we spotted one cave, then many more.

The 20-mile walk back towards Chitral, with mapping, noting, photographing and collecting from the caves occupied us for a couple of days. Disappointingly the largest [cave] penetrated a mere 20ft into the gorge wall and others were hundreds of feet up sheer rock faces.

Walking back, we had decided to hitch a lift on the next passing jeep and after some hours thought it strange that none had passed in either direction. About 10 miles from Chitral we discovered the reason. [There had been no rain where we had camped but] the road had been washed away in three places by overnight flooding. We had to scramble up onto the scree high above the river to bypass the places where the torrent had torn away the road. [We were wearing climbing boots but] with bulky packs on our backs and no firm handholds we scrambled awkwardly, realising that one slip could have set us tumbling into the boiling water, 150ft below. We felt a little less like intrepid mountaineers as the locals trotted past in plimsoles or sandals carrying briefcases or large loads for market.

They walked on the loose sand and sliding scree as if they were walking up stairs and shouted across to me “No dangerous, mister!”

In Chitral mudflows said to be ten feet high had swept down from the mountains and buried crops. The river had nibbled at the main road and swept away bridges.

Despite the air of disaster life was pretty much as normal and it was business as usual in the bazaar. It seemed that although the road back over the Lowari pass had gone, we should have little problem in driving to another limestone (and hopefully cavernous) area in Chitral district – the three valleys of Kafiristan inhabited by, so legend says, Alexander the Great’s descendants: the Kafir Kalash.

¤

The next leg or our journey was interrupted when locals asked us to unload before crossing a flimsy wooden bridge. It creeked and crunched alarmingly even under the weight of the empty Land Rover.

Further on we had to close the windows at every hairpin to keep out our own private dust cloud. Each bend seemed to present a different challenge. The wheels would creep to within inches of the crumbly road edge on many three point turns where the drop was often as much as 1000ft.

One particularly badly rutted hairpin had us see-sawing on two wheels – they were a hair-raising couple of minutes as we gently encouraged the Rover back onto four wheels and on up the track.

Once we had arrived in Bumburet – the largest of the Kalash Valleys – we decided to treat ourselves to the delights of the Tourist Hotel: “cheapest and best”.

We took over one of the two hotel rooms, tastefully decorated with a starting handle and on the mantlepiece an empty mango squash bottle and 20 or so dead batteries. The damp packed mud floor was, I believe, responsible for the pervading odour of mould and the only running water was in the gutter outside.

Apart from being rudely awakened soon after dawn by a donkey and a transiter radio endeavouring to outdo each other we slept well.

We rose to find our host squatting in the fireplace cooking our breakfast while he skilfully spat onto the mud floor at intervals. The thought of chapattis with white cheese and sweet tea stewing over beautifully scented burning pine whet our appetites.

It did not take us long to come to the conclusion that Kafiristan had no caves to speak of either, but three hundred feet up the cliffs that line the Bumburet Valley we spotted what appeared to be a mine entrance.

¤

Thinking this might lead to some natural cavern we climbed up only to find that the entrance was completely inaccessible. Returning with ropes we struggled to a point that we guessed must be above the mine. The rock was very loose – a mountaineer’s nightmare.

I had a near miss when I pulled a four-foot slab down on myself. Fortunately the rock only hit my leg a glancing blow and left me clinging to one firm handhold. I worried the others almost as much as myself as the first they knew of the incident was a body-sized thud [and the slab cartwheeling down the mountainside].

Abseiling down the rope until I was opposite the cave entrance was straightforward but getting enough swing to pendulum in caused problems. Dangling with 200ft of fresh air beneath, I began to wonder how much the rope had abraded during my descent. Swinging, of course, would do even more damage.

After several attempts to swing in I was standing inside the cave. It turned out to be a natural cavern just 10ft long and 7ft wide and had that lived-in look: food debris, soot on the roof, the remains of a door and a levelled floor.

We supposed that at some time, there must have been a kind of causeway giving access to the cave, but why anyone should want to live in a hole with a 200ft sheer drop outside, I do not know – a room with a view perhaps.

The Kalash Valleys were so cool, green, and peaceful that we decided to stay for a week or so despite the absence of caves. For economy’s sake we left the hotel and camped further up the Bumburet Valley and within 10 minutes we were surrounded by smiling Kalash boys.

I noticed one with nasty scabs on his face so treated them. Next morning 20 more girls and boys with this skin disease were asking for “da-wy” (medicine).

The word spread around the Kalash community and soon people with rheumatism, vast mouth abscesses, warts, cataracts, ear infections, two and three year olds with incredible louse infestations, and even people with sick goats were coming to me for help.

Many had been suffering for years and had walked considerable distances in the vain hope that European medicine could cure them. It was heart-breaking to turn them away.

In the valleys most of the medical treatment was by the poorly trained at the civil dispensaries. In Bumburet they we so poorly stocked that the local dispenser walked up to ask me for medicines!

¤

There are only a little over 2000 Kafir Kalash; their name means wearers of black robes. Their religion involves elaborate and beautiful dances for the rain and the crops and goat sacrifice in primitively carved temples.

Their language, culture and costume sets these people apart from the Muslims who inhabit Kafiristan.

Relations between Muslim and Kalash are poor. The Kalash accuse the in-comer Muslims of stealing goats and are dissatisfied with Muslim justice. The Kalash object to having to learn only at Muslim (state) schools – but these are the problems of minorities in many countries.

Our permit to stay with the Kalash forced us to leave after eight days.

In this short time we had all grown to love my “patients” however much they smelt! It was a rude shock to return to the clean but sometimes insolent and intrusive youths of the Punjab.

The Kalash were rascals, out to scrounge all they could but at the same time they were generous with what little they had to give: apples, walnuts, mulberries, time and friendship.

As the Land Rover headed south again we realised how much these happy people had taught us and we thought on how much damage the tourist invasion would do to the valleys during the next year or so.