From Manbu we could see across a steep valley to two more villages where PHASE works. It was quite close as the crow flies. I learned that the further one was about 200m higher than Manbu. However, the descent and ascent necessary to reach it on foot looked murderous. The walk up to Manbu had proved a bit challenging but I was keen to see more of PHASE Nepal’s work and joined others on the continuing journey. The main path onwards did a contour rather than plunged right down to the valley bottom but even so I found the walk to the next village of Yarsa a challenging four hours. Here we looked at some of the agricultural work that

PHASE was leading, having introduced polytunnels, simply sheets of clear plastic secured over bamboo hoops to form greenhouses. Before this innovation the villages had been able to grow little more than millet and potatoes but now their diet is much improved. The community are already used to co-operating during harvest time and were working well together rebuilding their homes.

Women were engaged with breaking rock to use as hard standing for each house and the men were bringing stone and doing the main construction. The co-operative working means that it takes only 15 – 20 days to complete a house.

From Yarsa we walked on – via a short stop at the school – to the village of Kashigoan where I spent a couple of days. The village has electricity but even during the winter there is no heating in the houses. The sunshine is warming but as soon as it drops behind the mountain ridges the temperature plummets and we found ourselves huddled in sleeping bags and under quilts as early as six in the evening. Even the local staff took to their beds to write their reports.

We were staying in a pukka concrete house but the loo was a low shed outside and we had to bring water in buckets to flush it. The bathroom and kitchen sink was a standpipe outside and the water bitingly cold, so my GP colleague and I mostly did what she called the prostitutes’ wash.

From Kashigoan the view was magnificent with dramatically steep green hills the foreground for Himalayan giants, but the landscape was scarred by innumerable need landslides. The local community had been fortunate in that few people had died in the quakes as the houses are small and it was relatively easy to get out into a safe space as the ground rocked and rolled but most of their homes were flattened. And one big landslide killed 100 sheep and their shepherd. Other villages weren't so fortunate; we heard that in the nearby village of Karuja, half the population died.

People slept under polythene sheeting for many months but their co-operative culture means they are recovering fast, especially now that, with the aid of PHASE-funded polytunnels, they are growing an impressive array of vegetables including the biggest lushest coriander I’ve ever seen.

My plan was to walk back down to Soti by the shortest route but my Nepali hosts said that the way was difficult. I have learned to listen when Nepalis say the path is difficult but anyway asked for more details and when it transpired that the difficult part was only 12m long, I thought I should manage and even suggested descending alone. That idea seemed to horrify my hosts.

Kiran, one of the local community motivators was volunteered to look after me and we set off with me feeling as nimble as an aging elephant while he danced down the path like an antelope, and even shinned up a tree at one point to pick some fruit for me. The route was mostly recently built steps through idyllic forest where we even met a troop of elegant langurs (aka leaf monkeys), but then we reached the part that PHASE were still working on.

One stretch of the path – which was scarcely 50cm wide – had been cut across what must have been a recent landslide and the mountainside at this point was almost vertical. The drop to the river below was a sheer 800m or so.

Next there was some dancing to do across piles of sand and concrete and rock slabs where safety rails would be built and then we got to the difficult bit.

I wondered if Kiran was joking at first when he indicated the way on. The path was narrow, substrate was loose sand and it was so steep that even the local workers needed a rope to go up and down it hand-over-hand. This was the 12 metres which interrupted access to the road and down which medical emergencies would have to be evacuated.

We in the UK with our ambulance service and accessible hospitals really don’t know how lucky we are.

|

| A polytunnel where villagers grow a range of vegetables |

|

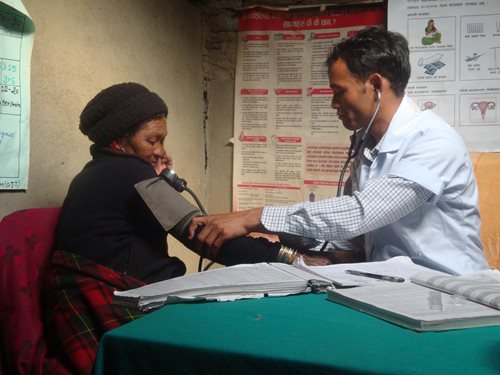

| Health Assistant, Lok, examining a patient in a PHASE-supported clinic |

|

| Communal post-earthquake house building in Yarsa, Gorkha District, Nepal |

|

| School at Yarsa, Gorkha District, Nepal; late November 2017 |

My previous two blogs about this trip are at

Admiring Swallowtails and

Village clinics