After the filthy atmosphere of Kathmandu, arriving in Wai was a breath of fresh air: it was easy to see this tight traditional community as a real Shangri La. The land was fertile, the air was pure, the turquoise Karnali River was close and mule-trains brought essentials and a few luxuries (bottled gas to cook on, soap, shampoo) to the little bazaar an hour’s amble on the other side of the valley.

The community was a long way from anywhere and I’d flown west from Kathmandu to Nepalgunj, then north in a twin otter from Nepalgunj to Bajura then walked east about three hours. I was there in November / December to observe and mentor clinical staff employed by PHASE Nepal. I stayed with them in the PHASE ‘office’, a four-roomed, two-storey building where the two Auxiliary Nurse Midwives and visiting Health Assistants cook, eat and sleep, do their paperwork and store medicines.

Early on in my visit I was sitting in the sun chatting to the landlord and, as 81-year-olds do, he was giving me his view of life. He told me that the keys to contentment were a good appetite, good sleep and good pissing. He also spoke with pride of the 19 members of his family: of the successes of his children and grandchildren had made of their lives. Mostly they lived Kathmandu.

|

| Our 81-year-old landlord enjoying the winter sunshine; he seemed so content with life |

|

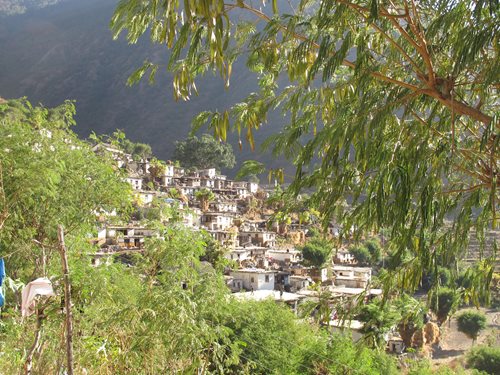

| The village of Wai snuggled in the hillside above the Karnali River in Bajura |

His statuesque wife busied herself as we spoke. The old couple’s neatly-dressed daughter-in-law lived in the next house and kept the mud-plastered area outside her home swept pristine so she could pound rice in a stone mortar set into the yard or she squatted to wash clothes in a beautifully crafted ground-level kitchen sink complete with an overflow that discharges into her kitchen garden, where coriander, chillies and African marigolds grow.

It seemed the perfect set-up with the daughter-in-law on hand to support the old couple. She sold us maize (to make popcorn) and crispy spinach from her terraces just outside the village. We shared with the old couple and their daughter-in-law a washing point supplied with water piped from a spring further up the mountainside.

The village of Wai is a cluster of 300 households, mostly square flat-roofed houses. In daylight hours there was the constant murmuring of a thousand voices with dogs barking, cockerels crowing and the twittering of bulbuls and tailorbirds. Come midday screams start up from distressed young humans. This isn’t and outbreak of child-abuse but of hygiene as toddlers and young children are washed in the cold, cold water running from various village taps.

By this time older children have donned their light blue and navy school uniforms and walked to school and those who have escaped both fates are absorbed in tree-climbing or games of chase or buffalo-teasing.

There seems to be a strong community spirit. Life seems idyllic with locally grown organic food ploughed by local oxen and fertilised by cow and goat dung; at the beginnings and ends of the day jingling bells announce the passage of goats and cattle.

After dark though there are strange other-worldly howling as jackals outshout village dogs. My clinical colleagues talk of the dangers of the night, including of jackal attacks. Others talk of spirits and ghosts.

When one morning as the sun rose soon after six, we heard wailing and dirges my friends told me someone must have died in the night. I wondered why we hadn’t been called. Then a little later our statuesque landlady unexpectedly launched into a tirade against her daughter-in-law, the gist of which was that she never helped with any chores and that she was lazy. This was when more of the family story came out.

The old couple’s son had left and was with a new ‘wife’ living in Kathmandu. Since polygamy was outlawed in 1963 and divorce is generally not allowed, except by an abused wife, surely the mother-in-law had no claims on her abandoned daughter-in-law? She didn’t believe so.

For me this story, the howling and the dirges made me see through my initial Shangri La mirage.

Life is hard in Wai. The nearest shops are an hour’s walk down to the river 500m below the village then across a suspension bridge and up the other side, and the return trip is tough if you need to bring heavy items; not that there is much to buy – nothing but a few wrinkled potatoes, onions and garlic. The diet is monotonous and often insufficient. Livestock deaths can threaten human lives too. I found the numbers of malnourished children we saw in the clinics each day truly shocking. As were festering wounds from mis-hits with knives or kicks by cattle and which were commonplace.

Life is tough in the Middle Hills of western Nepal.