When the pandemic was first seriously kicking off in March 2020 my husband, Simon, and I were in Kathmandu. Simon was leading a multidisciplinary team of around 100 rebuilding after the 2015 earthquakes and I was making myself useful writing clinical guidelines and mentoring paramedics. Both Nepal and the UK were locked down and it looked like chaos was about to engulf the world. We took a rather snap decision in April to join one of the three evacuation flights organised by the British Embassy. The air con was wound way up so the cabin temperature was c-c-c-o-o-old. We were provided with a bin-bag containing bottled water, crisps, biscuits and chocolate. The cabin crew kept away from the passengers, there were no in-flight films and we were discouraged from leaving our seats (even during refuelling in Dubai) so my bum felt flat by the time our 14-hours of flying was over.

I wasted no time in offering my medical skills assuming that an experienced GP would be useful in the crisis so I contacted various GP surgeries who know me, and the Out of Hours Service but during the rest of 2020 I was only offered work for eight days. Then in the new year I thought I’d volunteer to vaccinate people. I was medical director of a travel immunisation clinic in Cambridge for 11 years so I have some skills. I offered to do anything and thought I’d marshal to begin with but could do that because my DBS certificate was just out of date.

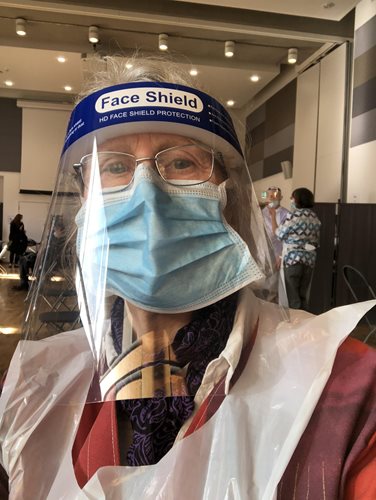

Then there was conflicting advice on what special training was required of me but I did hours of on-line courses and assessment. Finally though, towards the end of February, I was deemed qualified enough to join various retired doctors and nurses and others and felt privileged to help with the outstanding vaccination push.

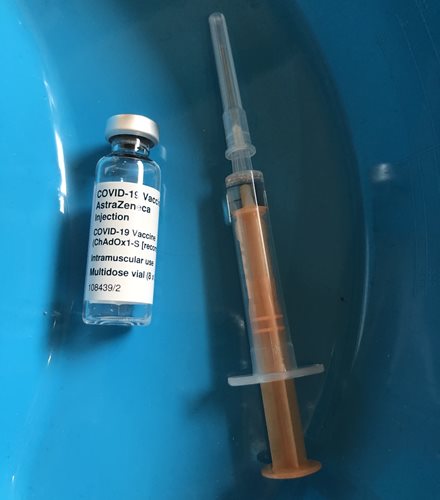

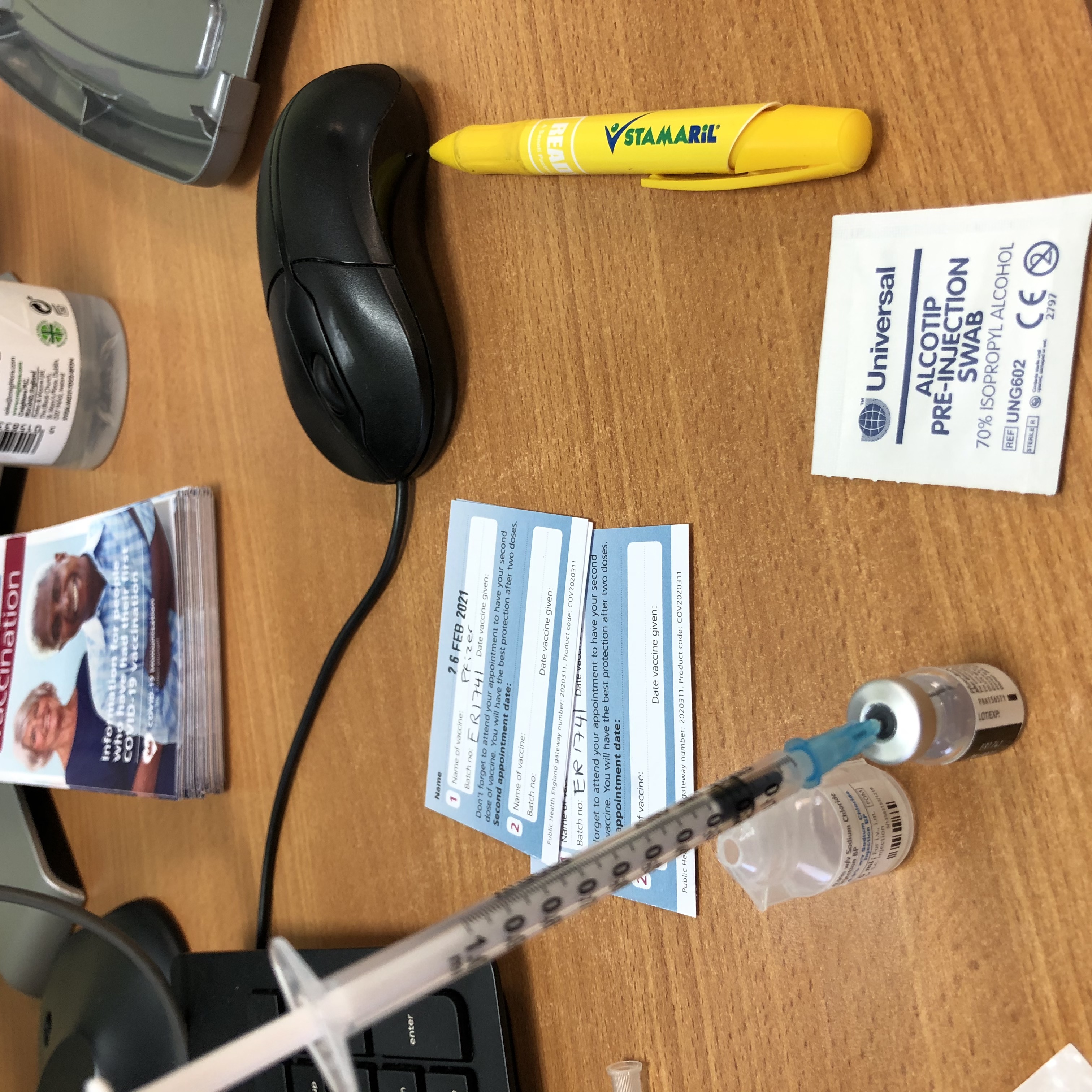

The work proved more intense than I expected. Some vaccinees had had very little human contact for 10 months and people really, really needed to talk. Yet our brief was to immunise person after person after person, and I was all too aware of queues forming as the words cathartically flowed from mouth after mouth after mouth. Teams of 7 or 8 clinicians would work relentlessly through the throngs of humanity, some weeping with relief to be getting the jab and in a half day of six or seven hours we’d vaccinate around 400 souls. The pharmaceutical companies are delivering vaccine as fast as they ca produce it, indeed at one session last week I was all geared up to vaccinate with the Pfizer vaccine – which needs diluting before administration so it is slower to deliver – to discover that the vaccine delivery expected in the morning for our clinic with patients booked in from 1pm didn’t arrive until 2.30pm. Fortunately there were some Astra Zeneca in the fridge to tide us over. I was glad I wasn’t in charge.

So because of delays in acquiring an up-to-day DBS certificate and finding out what training and then doing on-line training meant that I only managed to work as a vaccinator five times, although no doubt vaccinations will still be going on when we return to the UK in the summer.

But for the time being we're in quarantine in Kathmandu, seeing what can be done from our screens here, mitigating our restless desire to be making ourselves useful.

|

| The Oxford Astra Zeneca vaccine is easy to give, is prefered by clinicians and represents more than 70% of vaccine given in the UK |

|

| The Pfizer vaccine needs to be diluted before being injected |

|

| Dr Jane in full battledress in Cambridge |